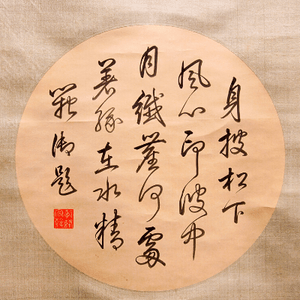

Beyond a form of writing, Chinese calligraphy is a form of art – and has been considered one of the most important forms of Chinese art for literally thousands of years. In fact, the integration of poetry, painting and calligraphy in a single piece of art is regarded as ‘three perfections”.

Being skilled in calligraphy (书法, shūfǎ) was a mark of being well-educated in ancient China. Not only did it demonstrate a deep understanding of the written language, but it also showed off the calligrapher’s eye for detail. The most skilled artists demonstrated excellent control over brush strokes and even composition of characters, while also writing with a fast but fluid style. And the best artists were able to show their personality through their calligraphy, too.

There are five main types of Chinese calligraphy script: seal, clerical (or ‘official’), semi-cursive (or ‘running’), cursive, and regular (or ‘standard’). Regular script is the most commonly used when it comes to artwork, while seal script is largely used for seals, which are widely used in many Asian countries instead of signatures. Clerical script is sometimes used for artwork, as well as sign writing. Semi-cursive and cursive scripts are flowier in appearance, with cursive appearing the most abstract and sometimes more challenging for some to read.

The one thing all of these scripts have is stroke order.

Chinese characters follow basic rules when writing them – whether with a brush or a pen. For example, characters are written from top to bottom, left to right, beginning with horizontal strokes followed by vertical strokes. But if a character has an ‘enclosed’ element, for example 回 huí, to return, the enclosure is written first starting with the left horizontal line in one stroke, followed by the top and right line in a single stroke. The bottom stroke of an enclosure is written last.

If a dot appears at the top or upper-left-hand corner of a character (for example 店 diàn, shop, and 话 huà, flower), it’s written first. But if it appears within or at the upper-right-hand of the character (for example 玉 yù, jade and 书 shū, book), it’s written last.

With enough practice, writing Chinese characters with the correct stroke order becomes second nature. And you can even work out how unfamiliar characters are written when using the same set of basic rules. But while writing characters out again and again on paper has been the go-to method of memorising characters for many years, calligraphy is also a great way to learn. That’s why children in China have calligraphy lessons as part of Chinese learning.

Not only does it help you learn the correct stroke order, but focusing on controlling the movement of the brush also helps you build muscle memory of the movements without even realising it. It’s really relaxing to do too, and can also be used as a meditation activity. And, of course, you have a beautiful piece of artwork that you’ve made yourself at the end.

Chinese calligraphy and ink painting happen to be two of the hobby activities Lingoinn offers. Why not add them to your Mandarin-learning adventure in China? Choose the Cultural Immersion Programme and add more activities for a memorable cultural journey.